Despite the weighty matter to contemplate following yesterday’s bombshell, and the freezing temperature, the night passed quickly and comfortably. Being outside in the courtyard had the advantage of not being awoken at dawn by the return of the family we were staying with. At just after 7 am Gyalbu brought me some tea and by then the sun was already warming the tent. Ah, the joys of a rest day!

Breakfast was an unexpected change from tsampa porridge, with or without meat and cheese, as our host’s wife made roti. The name ‘roti’ is derived from the Sanskrit word for bread: rotikã. The roti is one of the most popular Nepalese foods. It is considered light and healthy and is normally served for lunch or dinner as it goes with just about everything including meat, vegetables and lentils. It is a flat bread. Not the buckwheat variety we were accustomed to but made from a wheat flour known as atta, with butter, salt, sugar, milk and water. Once kneaded and separated into small balls, the dough is flattened with a rolling stick into small circles and cooked on a flat iron pan called a tawa. Once it is cooked and a number of small air pockets have appeared so the bread starts to puff, it is taken from the pan and served hot. In addition to savoury, roti also goes well with sweet foods so we were doubly in luck as the family had some jam. What a treat! A roti spread with a little butter (yak butter naturally but good all the same) then smothered in jam, followed by another, washed down by normal black tea with a little sugar. The day was starting well indeed. We would need to discuss the way forward, but not until later as there were a few more enquiries to be made first.

After breakfast I headed out for a walk. Although this was a rest day I wasn’t actually tired and my camera, i.e. my iPhone, had been playing up yesterday and I hadn’t been able to capture all the pictures I had wanted. It was now fixed and that was all the excuse I needed to get back into the mountains for a couple of hours, retracing our steps from yesterday. The ever thoughtful Gyalbu offered to come with me but that was declined as his skills would be better employed trying to find a way for us to continue on our origninal route. Apart from which I was looking forward to some space to myself, to think about our dilemma. As I was leaving at just after 9 am the lady of the house was doing the washing up.

After giving Tim my route and return time I crossed the river and went back up the treacherous path descended yesterday. My whereabouts would have been seen clearly by the others as I zig-zagged up the mountainside then disappeared along the cliff to the left and into the valley. The sky was blue, the sun was hot and I was in my element.

The blue sheep (bharal) were still there on the other side of the valley, although fewer in number, and I stopped for a while hoping to catch a glimpse of a snow leopard. But there was no sign – hardly surprising given naturalists spend weeks in a hide without more than a glimse. The sheep continued their leisurely grazing without disturbance, so after a few minutes I moved on. Past the frozen waterfall I went at a good pace even though the route was uphill all the way. After an hour and a half the Khoma La was just ahead and I was tempted to go to the pass but I had assured Tim I would be back by 11:30. Doing the sensible thing for a change I turned round and headed back to Saldang, downhill at speed through the dust. I reached the village just in time having not seen any people, or any animals other than the distant blue sheep. Once again the mountains were empty.

Once back at the house there was time for some washing. While my t-shirt, socks and underclothes had been rinsed and either dried in the sun or put back on wet a couple of times, my trousers had been worn from the start. I, as had others, felt it pointless to put on clean trousers as dust and dirt was everywhere and anything clean would be filthy again in no time. There were limits however and today was the day my lightweight trekking trousers got washed and my spare trousers had an airing. The spares, a pair of Haglofs mountaineering trousers, were much thicker than my trekking trousers as they were brought not only as spare trekking strides but to cope with colder weather. Thankfully the trekking trousers dried very quickly in the sun and were back on before the end of the day.

After the trousers were washed it was my turn. There was no bathroom of course but there was a toilet measuring around 1 yard by 2, with a closing door and a brick missing in the wall to let in some light when the door was closed. At one end of the toilet was a large green plastic bucket. It was about 2.5 times the size of a normal bucket and contained water for ‘flushing’ the toilet. The toilet itself was a ‘stand-up’ but there was at least a plastic insert leading to a soakaway, rather than a longdrop. Once the facility had been used, water was taken from the large bucket with a jug and used to sluice the toilet clean. The point of all this discription is that I could stand in the large bucket and pour water over myself using the jug and thereby have a bit of shower. Despite the missing brick in the wall there wasn’t much light so the door was left a little ajar and everything went fine for a while. The issue was that the floor of the toilet room wasn’t level and half way through my ‘shower’ the bucket in which I was standing overbalanced. I faced having my head or shoulder dashed against a wall while my feet were still stuck in the bucket so managed to very quickly get one leg out. Unfortunately the only place for my foot go was into the toilet. So there I was, now with one clean foot, the rest of me soapy, and the other foot in desparate need of another wash! At least I had saved the whole bucket going over and losing the rest of the water so the ‘shower’ could continue, with more care being exercised. Once dried and dressed, and after having re-filled the bucket, I actually felt clean for the first time in over a week.

By then it was lunchtime, after which we needed to decide the future of the trek. This had been on everyone’s mind all morning but it had not been mentioned.

We gathered on the steps of the house in sunshine while Tim re-capped the issues raised yesterday. Tim then said that he had found another potential route by which we could get to Jumla. He called it the jungle route as it avoided the most mountainous region and the multiple high passes between Pho and Tiyar and we could see it on the map. The term ‘jungle’ was just an expression. The route was still high and followed river valleys some of the way but included at least 2 high passes. We wouldn’t go below 3000m until we reached Tiyar. The benefit was that, being a little lower than the Great Himalayan Trail route, the rivers shouldn’t be so frozen and it might be feasible for us to do without ponies if we carried our own big packs. However the people he had spoken to in Saldang were unsure whether it was usable. One had said the path had fallen into disuse and following the earthquake climbing equipment might be needed to get through. Another said it might not be that bad but he wasn’t aware of anyone using it since the monsoon earlier in the year. We concluded that it might be viable but we needed to get closer to find out. Perhaps the people in Bhijer, the next village, would know. Or perhaps we would need to go to the village beyond Bhijer, to Pho itself where the path started, to get some reliable information with which to make a decision.

Anticipating this, Tim earlier had another discussion with our horseman to see if he would go to Pho. He had agreed to go to Bhijer, as there was a route south to Juphal from Bhijer, but he would go no further north, including to Pho. This meant that if there was reliable information in Bhijer we could make a decsion there tomorrow and not prematurely today. If we could find ponies or mules in Bhijer with a horseman willing to go north then the original route remained possible. If the local advice was that the ‘jungle’ route was passable then that alternative could be adopted. Ideally we would find a horseman with a string willing to support us but if not then we could still attempt to get through unsupported.

A third new matter was raised then. During his discussions this morning Tim had learned that there was now a road from Jumla to Rara, just west of Gamgadhi. The impact of this was that the final 40 miles of our trek would be beside a road, where a ‘road’ in these parts just means a flatten strip of terrain covered in grit and deep in dust. We all recoiled as we remembered very well what it was like on our acclimatisation walk from Kagbeni to Jharkot and back. Constantly being showered by dust a grit by passing motorcycles and toiling buses belching oily exhaust fumes. Three days of that would be miserable. Maybe we could hire a car? Maybe, but that wasn’t what we came to Nepal for.

After about an hour of discussion, and in truth a degree of arguing, we were agreed that trying to go north without support would be foolhardy and that had been ruled out. However there was no concensus on the best alternative. We were split between those who still wanted to try the ‘jungle’ lower-level route from Pho to Gamgadhi via Tiyar, those who felt that taking the escape route south to Juphal either from here at Saldang or from Bhjer might be less risky, and those who would be happy with either route. In light of this we decided to put off further discussion for a while and go for a walk around the village.

Further up the mountainside to the upper part of the village we found a monastery. The buildings were in good repair, and included the monastery itself and living quarters for the monks in ochre and white with gold-painted roof and chimneys. There were also several large chortens, both 2- and 3-tier, also in ochre and white decked with prayer flags. But there was nobody home.

Somewhat incongruously, a little further up the hill was the Tashi Samling Guest House. At the bottom of the sign in white lettering on a red background it advertised: “We facilitate lodging, fooding (sic) with typical Dolpo dishes in a homely environment”. The sign was flanked by animal skulls. We knocked enthusiastically on the door but without answer. It was closed and empty.

At the top of the village we found a large house that was occupied. We were invited in, entering the courtyard through a door on which had been roughly painted in multiple colours “WELCOME TO MY HOUSE”. It turned out to be the headman’s house, which explained its size and relative opulence. We were shown upstairs and through the light and well stocked kitchen, past the family prayer room, into a side room where we were seated on rug-covered benches either side of a table. At one end of the room was a shelf unit bearing goods for sale, including jars of BournVita, drinking chocolate, honey, jam and (joy of joys) peanut butter. There was also a selection of drinks, inevitably including Lhasa beer and Coca-Cola, and a selection of household goods and sundries. Chuckling at the little camouflaged fishing chair we promptly bought 2 jars of peanut butter and some jam, but elected to try this family’s Raksi rather than drink Chinese beer.

While we were enjoying the very good Raksi we heard “morning” from the kitchen. Then a little boy appeared, clothes still as grubby as the few other children we had seen these past days but otherwise looking uncommonly clean. He had twinkling eyes and a cheeky smile and when we smiled back he repeated “morning”. We collapsed in laughter, and all chorused back “morning” (even though it was mid afternoon). The little fellow was delighted and chirped a third time “morning”. Then his mother said something from the kitchen and he scampered off. We didn’t see him again but “morning” wasn’t forgotten.

Then the lady appeared again with a metal bowl half-filled with potatoes which had been boiled in their skins in salted water. We were invited to try some. They were absolutely delicious. She put the bowl down on the table and it was clear they were for us to buy if we wanted them, which we did. They were all devoured.

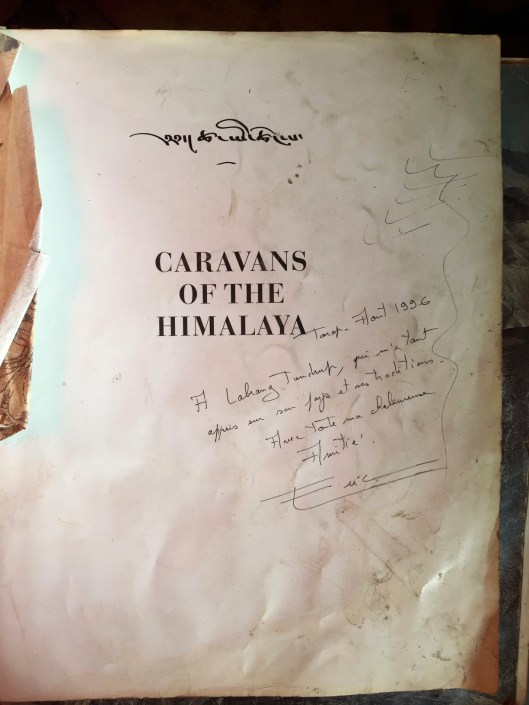

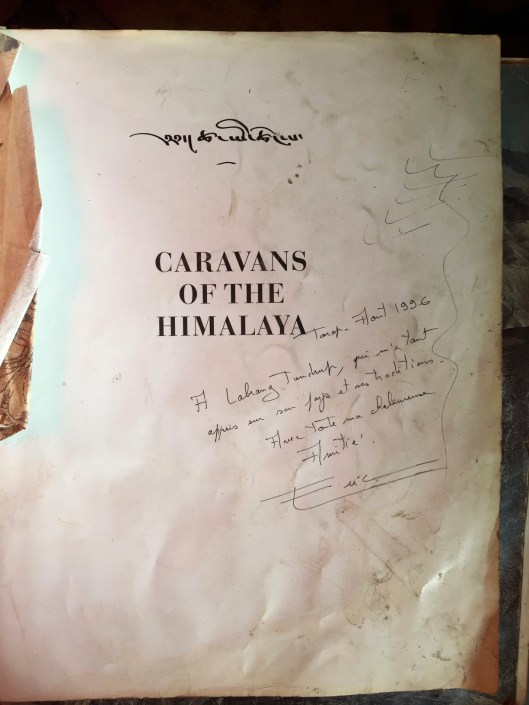

Then the headman himself appeared and introduced himself, in Nepali of course but Tim responded for us while we limited ourselves to Namaste and Tashi delay! He then went into the prayer room and returned with a large book that had been well thumbed. To our astonishment it was a signed copy of the Frenchman Eric Valli’s ‘Caravans of the Himalaya’. The evening before I left London for Kathmandu I had watched, with Clare, Eric Valli’s beautiful film ‘Himalaya’. The film sleeve says “at an altitude of five thousand metres in the remote mountain province of Dolpo, Himalaya is the story of an ancient tribe who lead a caravan of yaks across the mountains, carrying salt from the high plateau down to the plains”. The book that the headman had showed us was the book produced 20 years ago to support the film.

The headman then turned the pages to a photograph obviously much admired and thumbed. It was of him! In the film! This man had a leading role in the film and had been given a copy of the book signed and dated August 1996 by Eric Valli himself, with a message of thanks to Labrang Tundrup. The village chief or headman, our host, was Labrang Tundrup, who played the character Labrang in the film. We talked for a while. He said the salt caravans were very rare now but his people still moved in the traditional way, in fact some had gone south only recently. We were stunned and captivated.

Labrang Tundrup was then called away. He transpired to be a doctor and he was needed to treat a woman who was now in the kitchen. He listened to her for a while then had her kneel on the floor. He reached into the fire and drew out an iron rod that was red-hot at one end. He held the other in a rag. Labrang Tundrup then spoke quietly to her and touched the rod to her head four times, once on her temple and once on the back of her head, then once more each side just above her ears. Each time there was a slight smouldering and a little smoke, but on no occasion did she react. When it was over she sat quietly for a few seconds then smiled brightly, looked very quickly in our direction, then she was gone. Apparently cured.

We had just had the most amazing experience and seen things very few had. We felt utterly privileged and simply looked at each other, speechless. After a while we talked again, reliving what we had just learned and seen.

By and by the talk returned to our intentions for the rest of the trek and an aspect that hadn’t really been explored. The discussion thus far has focused on the original plan and its new variants. We had spoken at length about the problems and risks of going north and the difficulties of the new route west. We hadn’t really explored the benefit of going south as it was simply an ‘escape route’. Now Tim gently introduced that option.

Although shorter it would be a tough route as there were still high passes to negotiate, however the villages that we passed were likely still to be occupied as they were lower. We would pass the Crystal Mountain, the spitual heart of Inner Dolpo, and the nearby 11th century Shey Gompa (monastery) near which Peter Matthiessen had seen a snow leopard. Then further south we would trek around Phoksundo, the stunningly beautiful freshwater lake which features in the film ‘Himalaya’. All the way we might have the opportunity to meet more people; an opportunity we would not have if we went north or east.

Set again this opportunity was the uncertainty and risk, some people we had asked used the work danger, associated with north or west. We were simply too late in the year. Winter was setting-in, the people were leaving and the water was becoming trapped in ice. We would have to rely on our own food and fuel without likely resupply. There were no ponies for hire in Saldang and the same was likely in Bhijer and Pho. If we tried without support and had to turn back towards the end we would be in significant difficuly without food or fuel and in some danger. We had rescue cover, GPS and a satellite phone but that wasn’t the point. Then there was the final 40 miles by, or on, the dusty road to Jumla. We had been lucky so far. We had good support, fine weather and no injuries or illness. Let’s not push that luck too far. If we were determined to finish the original route we should do it when the probability of success was higher, earlier in the year. Another year.

We decided there and then, in the room where we had been enchanted by the doctor and Headman of Saldang, Labrang Tendrup, welcomed and fed by his wife, and delighted by his grandson “Morning”, to prioritise cultural experience over ‘a foolhardy walk into the jaws of death’. We laughed heartily, shook hands and hugged, and sealed the agreement with Raksi.

We were going south!